Why is January 10 so important to Venezuelans?

And a recap of the last 26 years (from a person who lived there for 23 years).

Para leer en español, haz click acá. :)

Is 2025 the year that Girlsplaining makes a comeback?

It’s been ages since I last wrote to you all. You might not even remember, but I used to explain complex or trending topics in a simple way through this outlet.

The truth is, I started this newsletter because I wanted to write more and use the articles as my portfolio. At some point, I got a full-time writing job, and doing both things was exhausting.

I also felt like I wanted to change it up a bit but didn’t know how. I guess that if I had my own space to share ideas, then I could use it to make it a bit more passionate but instead of figuring out how to change it, I simply abandoned this.

Anyways, I’m not going to overwhelm you with my personal life—I don’t even know how often I’ll write. But, with January 10 around the corner, doing an edition about Venezuela’s situation seems like a good way to deal with the anxiety that comes with growing up under a dictatorship.

Also, the other day a friend (not Venezuelan) told me: “You never have anything good to say about your country.” That stuck with me because I love Venezuela, and I’ve been trying to reconnect with my Venezuelan identity for months. However, it’s also true that Venezuela hurt me in ways I still don’t fully understand, and those wounds surface from time to time—I guess I’m still healing (?).

Yesterday, another friend (Venezuelan) said: “I’ve learned to separate Venezuela from its politicians because Venezuela is amazing, but they aren’t.” And I think it’s now my job to figure out which of the beautiful things about Venezuela live inside me, beyond the trauma.

So, let’s get to the point: Why is January 10 so important? I’ll explain it in simple terms so you can share it with others and avoid defending a dictatorship (embarrassing).

Note: I’m writing this freely because I live abroad. I also had to leave out a lot of data for the sake of time and length. This is a summary of what I consider/remember to be the most important points. You’re more than welcome to share any relevant ones in the comments.

Venezuela’s dictatorship and January 10th

If you’re close to a Venezuelan, I probably don’t need to explain what’s happening in the country. If you’re not, here’s a brief recap of everything that’s happened in Venezuela over the past 26 years.

There’s a TL;DR in the end in case this version is still too long.

Chávez’s first government

Chávez won the 1998 elections after attempting a coup against the then-president Carlos Andrés Pérez in 1992.1 He was imprisoned, but two years later the then-president Rafael Caldera couldn’t read the red flags, pardoned him, and released him from prison.2

The truth is that Chávez came to power because he promised to be the voice of the poor, which accounted for more than 45% of the population.3 I wasn’t even born back then, but from what my parents have told me and what I’ve read, Venezuela was a livable country only for the middle and upper classes.

There were no social programs or assistance of any kind. Popular areas were completely neglected, and Chávez rose to power with the promise of giving the lower class the recognition they deserved. (This is why he’s beloved in the rest of Latin America.)

But, surprise, surprise: A politician lied.

In his early years in office, instead of fulfilling his promises, Chávez began to reveal his authoritarian tendencies. By mid-1999, he created a National Constituent Assembly to replace Congress, with the aim of reforming the constitution.

The constitutional reform was pitched as a way to make Venezuela less centralized and more federal. However, what actually happened was that he changed:

The country's name to “Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela”

Extended the presidential term from five to six years

Approved the indefinite re-election (not exactly giving democratic vibes)4

Chávez’s second term

The Constituent Assembly approved an Enabling Law (essentially granting Chávez superpowers), allowing him to modify 49 laws by decree. *Not-so-democratic vibes intensify.*

The 2001 Organic Hydrocarbons Law was among those 49 laws.5

This new law gave the state greater control over resource exploitation and increased the percentage of oil royalties payable to the state—from 16% to 30%. This angered PDVSA, Venezuela’s largest oil company and the main contributor to the GDP at the time, creating a tense social atmosphere.6

Venezuelans were upset by Chávez’s desire to bypass Congress and give the State so much control. The final straw was when Chávez fired PDVSA’s executive board live on national TV. On April 7, 2002, the president called by name each of the executives who were fired for opposing Chávez’s mandates.

These actions led to a massive protest on April 11, 2002. The march re-routed and ended up turning toward the Presidential Palace in Miraflores to demand Chávez’s resignation. As people protested in the streets, a group of military officers, led by Vice Admiral Héctor Ramírez Pérez, went on national television to declare they no longer recognized Chávez as president.

Paramilitary groups began attacking protesters with weapons (rumor has it these groups were led by Maduro, who allegedly fired at the crowd himself). Nineteen people were killed that day.

Around 3:00 a.m., General Lucas Rincón Romero, Chief of the Armed Forces, announced on television that Chávez had resigned. By 4:00 a.m., Chávez was escorted out of Miraflores. However, on April 13, Pedro Carmona, who was set as the replacement, resigned, and Chávez returned to power.7 (Fun fact no one cares about: on April 13, I was celebrating my 7th birthday with a piñata and no one could attend my party.)

At the end of 2002, in an attempt to push for Chávez’s definitive resignation, PDVSA led a 62-day oil strike. It escalated into a general strike, as there was no fuel. There was no public transportation or ways to transport food to grocery shops and people couldn’t go to work or school. Over time, the strike weakened, and life returned back to normal.8

Around this time, Chávez started talking about the Missions—social programs aimed at increasing literacy, providing public healthcare, and subsidizing housing. However, these were only partially implemented after the failed coup and strike in 2003.9 While some people finished school, gained access to healthcare, or received housing through these programs, the missions deteriorated over time and are now nearly nonexistent.

During his second period, Chávez began expropriating companies—over 1,200 during his time in office. The state became increasingly controlling.10

In 2003, people signed a petition to trigger a recall referendum to remove Chávez before the end of his presidential term. However, the petition list was illegally published by a pro-government congressman (Luis Tascón, a massive snitch).

As a result, since the State was now the owner of all big companies, Chávez fired everyone on the list from state-owned companies. The government claimed that signing the petition was “a terrorist act.”11 I couldn’t find the footage, but people remember that this was also broadcasted live on national TV. Chávez named each person by name and then blew a whistle indicating they were “out” of the company.

Nevertheless, the recall referendum was held in 2004 and Chávez won. The opposition claimed the government had committed fraud and refused to participate in the National Assembly elections—which gave Chávez’s party free rein to rule the Assembly.

Gradually, the separation between political parties and government eroded, and the regime became increasingly authoritarian.

Chávez’s third government

The government nationalized the largest telephone and Internet company in the country (CANTV) and a mobile phone company (Movilnet). It refused to renew the broadcasting license for the opposition TV channel RCTV, and the sanctions from CONATEL (the agency that regulates media) became more severe.12

Taylor Swift would say: “I’ve never heard silence quite this loud.” And that’s how I remember this period, it was the censorship era. Saying anything against the government was penalized and even when it wasn’t, people were so afraid to speak that they stopped talking about politics on TV, radio, and even online.

At the same time, Chávez expelled the U.S. ambassador from Venezuela and started breaking up its relationship with the States. Also, the globe started calling out Chávez for rights violations and signs of authoritarianism.13

In 2009, there was a new referendum to reverse the presidential term back to five years. The opposition won, but Chávez said it didn’t matter and declared he would stay in power until 2021.

The presidential term was set to end in 2013, and Henrique Capriles was preparing to become the opposition candidate in the elections. Chávez was diagnosed with cancer and went to Cuba for treatment. In the presidential elections held in 2012, Chávez won with 55.07% of the votes.

At the end of 2012, Chávez appointed Nicolás Maduro as his vice president and died in March 2013, leaving Maduro in charge. New elections were held 30 days later—Maduro vs. Capriles—and Maduro won with 50.61% of the votes. The opposition declared fraud, but no one was ever able to prove it.14

Over time, images of Chávez’s eyes started to appear painted all over the country. (Big Brother vibes).

Maduro’s era

At this point, I don’t even know what happened anymore, but everything went to hell. To keep it short, I’m going to condense both terms into one.

Maduro had the Enabling Law to rule by decree on several occasions. During this period, corruption increased, and bribes from the company Odebrecht to Venezuelan officials came to light—the total amount was nearly $100 million.15

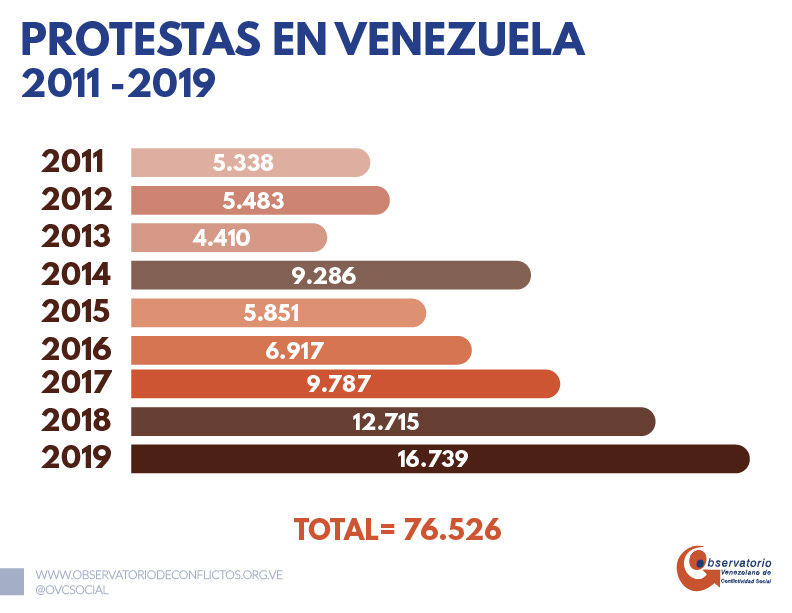

During this era, Maduro lived through three major waves of protests in 2014, 2017, and 2019. He dealt with these events with highly violent repression and police brutality. Most people who are incarcerated due to protest go to the Helicoide, the world’s biggest torture center.

In 2014, civil protests lasted from February 12 to June 1. People marched against shortages, insecurity, and inflation. This resulted in the imprisonment of opposition leader Leopoldo López.16

In 2017, protests lasted four months. They were partly for the same reasons as in 2014 but also because the Constituent National Assembly stripped parliamentary deputies of immunity and began politically disqualifying opposition leaders.17

In 2019, there were over 16,700 protests across the country. People demanded a change in government, living wages, access to healthcare and food, and improved public services.18

Between 2018 and 2019, Juan Guaidó, the president of the National Assembly, declared himself interim president of Venezuela, stating that Nicolás Maduro’s 2018 reelection had been fraudulent. Guaidó was recognized as interim president by more than 50 countries, including the United States and several European and Latin American nations.19 Afterward, he raised a lot of money for humanitarian aid and disappeared.

In March 2019, there was a nationwide blackout that lasted more than 140 hours. One afternoon, the power went out across the country and didn’t return for several days. There was only signal in certain areas of the cities; in Caracas, people parked their cars on the highway to get signal and let their families know they were okay. The only way to buy food was using dollars in cash as it’s almost impossible to get bolivars from an ATM—only places with generators were open. Public hospitals didn’t have generators, and many people died because they were not connected to respirators.

Diosdado, the president of the Constituent National Assembly, blamed Guaidó and the U.S. for the blackout. “What he’s done [Guaidó] caused harm by asking for sanctions, asking for a blockade, asking for the power to be cut off in hospitals,” he said.20 Although the power system was already failing years before that.

After the U.S. sanctions, the “enchufados” (people who stole money from the government) started investing money in the country. Now, it’s possible to drive through Caracas and see huge buildings, casinos, luxury cars, and expensive restaurants. Needless to say, most people don’t have access to these things as the minimum wage is 130 Bs. ($2.51).21

Protests, shortages, the economy, insecurity, and a thousand other reasons led nearly eight million Venezuelans to migrate to other countries.22

Finally, in July 2024 Venezuela had presidential elections. Here’s a very quick explanation of who is who:

Nicolás Maduro—current dictator of Venezuela. Has been ruling for 11 years. Is responsible for the disappearance, tortures, and murders of thousands of Venezuelans.

María Corina Machado—opposition leader who’s had a career in politics since 2011. She was supposed to be the true candidate after winning private primary elections, but the regime disqualified her as a politician. However, she led the complete plan to win and fight for Venezuela’s freedom.

Edmundo González—opposition’s candidate. He’s a former diplomat who served as a decoy for the elections. Since Maria Corina was disqualified, her party signed him up for the run as a way to secure an opposition candidate that could run. He ended up becoming the candidate and winning the elections.

Why is January 10 so important

In last year's elections, the National Electoral Council (CNE) declared Maduro the winner with 52% of the votes. After years of elections with little credibility, the opposition, led by María Corina Machado and Edmundo González, made a plan to collect the voting machine records. This allowed them to prove for the first time in history the electoral fraud.

In those records, the only ones published so far, Edmundo won with 67% of the votes.23

Since July, María Corina has been in hiding, changing locations regularly to avoid being arrested by the government. Edmundo had to leave the country due to threats. There were lots of protests that resulted in the government removing people from their homes for protesting or sharing opinions on the internet. More than 1,800 people were imprisoned—150 are minors. Only 70 adults and 85 young people are free today.24

The same happened to journalists and media outlets. In many cases, arrest warrants were issued, and then policemen asked them to pay USD 4,000 to avoid being arrested.25

I could keep listing misfortunes, but let’s focus on the important stuff. On January 10th, the new president is supposed to be sworn in. Maduro says this change is illegitimate because he won the election, but the only one who presented evidence was Edmundo. On the other hand, the CNE never shared the records, didn’t allow international observers, and Elvis Amoroso, the president of the CNE, is openly chavista.

Political persecution worsened, and on January 7th, the government kidnapped Edmundo’s son-in-law while he was taking his children to school—the kids were in the car.26 María Corina also reported that there were soldiers surrounding her mother’s house and that “the power went out.” “She’s 84 years old, sick, with chronic health issues. (…) Maduro and company, you have no limit to your evil. Cowards,” she shared on Twitter (I refuse to call it X).27

Edmundo, from exile, promised to return to Venezuela on January 10th to swear himself in as the legitimate president. He has met with presidents from other countries like Argentina, Paraguay, Panama, and the U.S., who recognize his victory. This week, Caracas woke up much more controlled with police in the streets.28

So, with the dictatorial vibes intensifying, we all wonder: What’s going to happen on January 10th?

I honestly have no idea. No one can imagine Maduro peacefully handing over the presidential band to Edmundo. Is there some military movement we're not seeing? Is there some sort of negotiation behind the scenes? Will nothing happen?

I think the last option is the most agonizing for everyone. So, if you have a Venezuelan close to you, hug them this week.

TL;DR:

Chavismo came to power with the promise of giving a voice to and helping the poor. At the time almost 50% of the population was poor, now more than 90% of Venezuelans are.29

What happened next is that Chávez transformed the constitution to support his authoritarianism. He expropriated more than 1,200 companies and took control of almost everything, including big companies and the media.

This wouldn’t have been a problem in a state with separation of powers or where each company had autonomy, but that wasn’t the case in Venezuela. After taking control of PDVSA, Chávez fired everyone who had voted against him on national TV.

After his death, Maduro was even worse. The country plunged into a severe supply crisis, insecurity increased, and protests grew stronger. Nearly eight million people migrated to other countries.

In 2024, there were elections. The head of the CNE was openly chavista and did not allow international observers. He also didn’t allow foreigners to register to vote from abroad. The opposition collected the records generated by the machines (which cannot be modified) and shared them with the world, showing that Edmundo had won. The CNE claimed Maduro won, but never shared proof.

Since then, political persecution has intensified. Edmundo went into exile, and María Corina had to hide in Venezuela. On January 10th, the new president will be sworn in, and Edmundo says he will return to swear himself in. No one knows what will happen.

Wikipedia. (I fact-checked this)

Wikipedia. (I fact-checked this)

Wikipedia. (I fact-checked this)